Order: Uropygi

Family: Thelyphonidae

Genus: Mastigoproctus

Species: giganteus (Lucas, 1835)

Common Names: Vinegaroons, Whip-Scorpions, Grampus, Mule Killer

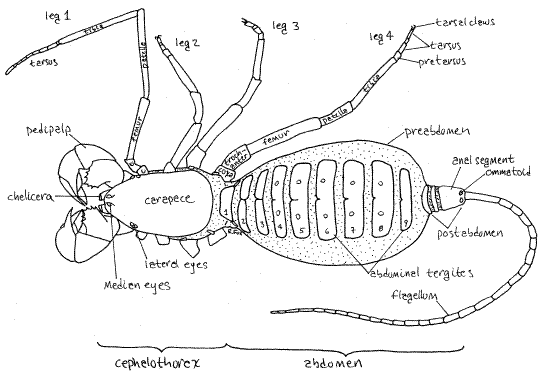

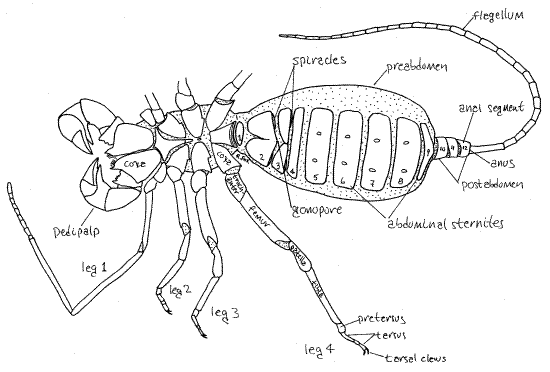

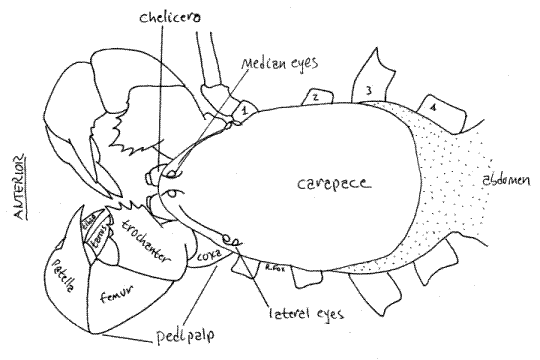

External Anatomy:Illustrations are actually of a member of the genus

Thelyphonus, but the external anatomy is basically the same.

Illustrations are the property of Richard Fox (Lander University) and were obtained here: http://lanwebs.lander.edu/faculty/rsfox/invertebrates/thelyphonus.html

Origin and occurrence: These are the only Uropygids native to the United States. They occur in the Southern United States from Arizona to Florida and south into Mexico.

Size: Mastigoproctus giganteus is the world's largest Uropygid. They can reach lengths of up to 3 inches (~8 cm) not including their flagellum or pedipalps.

Lifespan: Their exact lifespan isn't known, but there is some indication they are fairly long lived. I can tell you from personal experienced that they are very slow growing. If I had to guess a lifespan, I'd say at least 10 years based on their growth rate.

Captive Conditions and Information:Cage Setup: As they are terrestrial burrowers,

M. giganteus should have a horizontally oriented enclosure with sufficient height to allow for at least 3 inches of substrate for burrowing. I also recommend adding a piece of cork bark (or something similar) for your

M. giganteus to utilize as a hide. They are unable to climb smooth surfaces such as glass. A 5 gallon tank is a suitable size for an adult.

Temperature: These animals are quite hardy and can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. I'd try to keep them around 75°F (~24°C) but really, whatever temp is comfortable for you will be fine for your

M. giganteus.

Humidity: As they come from more arid environments, humidity isn't much of an issue. Adults are quite tolerant of relatively dry conditions, but water dish should always be available and the substrate should be kept slightly moist. For younger individuals, a plastic water-bottle cap may be used as a water dish, or they can be kept on moister substrate than adults until they are large enough to drink from a water dish. You may also lightly spray the tank to provide water to young individuals.

Substrate: The substrate should be at least 3 inches of a 50% coco fiber or peat, 50% sand mixture that is kept slightly moist. Pure coco fiber may be used for very young individuals as it holds moisture better than a sand mix. If you do not provide substrate deep enough to allow for burrow construction, then you should give them a cork bark shelter to hide under during the day, otherwise they will wear themselves out trying to dig a burrow.

Feeding: I feed my

Mastigoproctus giganteus once every 7-10 days. They capture prey by crushing the prey item with their spiked pedipalps. They do not possess any venom. Marshall noted that "they feed well on insects and can become so fat they may actually eat themselves to a standstill!" Good prey items are crickets and B. lateralis roaches.

A young individual eating a cricket:

Behavior:

Behavior: These animals are nocturnal, wander around in darkness and feel their surroundings using their first pair of legs, which have evolved into highly sensitive antenniforms. I find

Mastigoproctus giganteus to be more active than most other arachnids. (Such as spiders and scorpions.) I often see mine walking around, especially if the room is relatively dark. They hide by day in their burrows or under rocks and logs, emerging at night to feed on smaller arthropods.

These animals are quite docile, but when threatened, they spray a acrid solution that is composed of 84% acetic acid (the basic component of vinegar) and 5% caprylic acid. (Among other substances.) Caprylic acid serves as solvent for the acetic acid, the mixture basically attacks the exoskeleton of arthropod attackers. The acetic acid is concentrated enough to cause mild burning. The odor that results has given rise to the common name "Vinegaroon." Some tropical species smell of formic acid or chlorine.

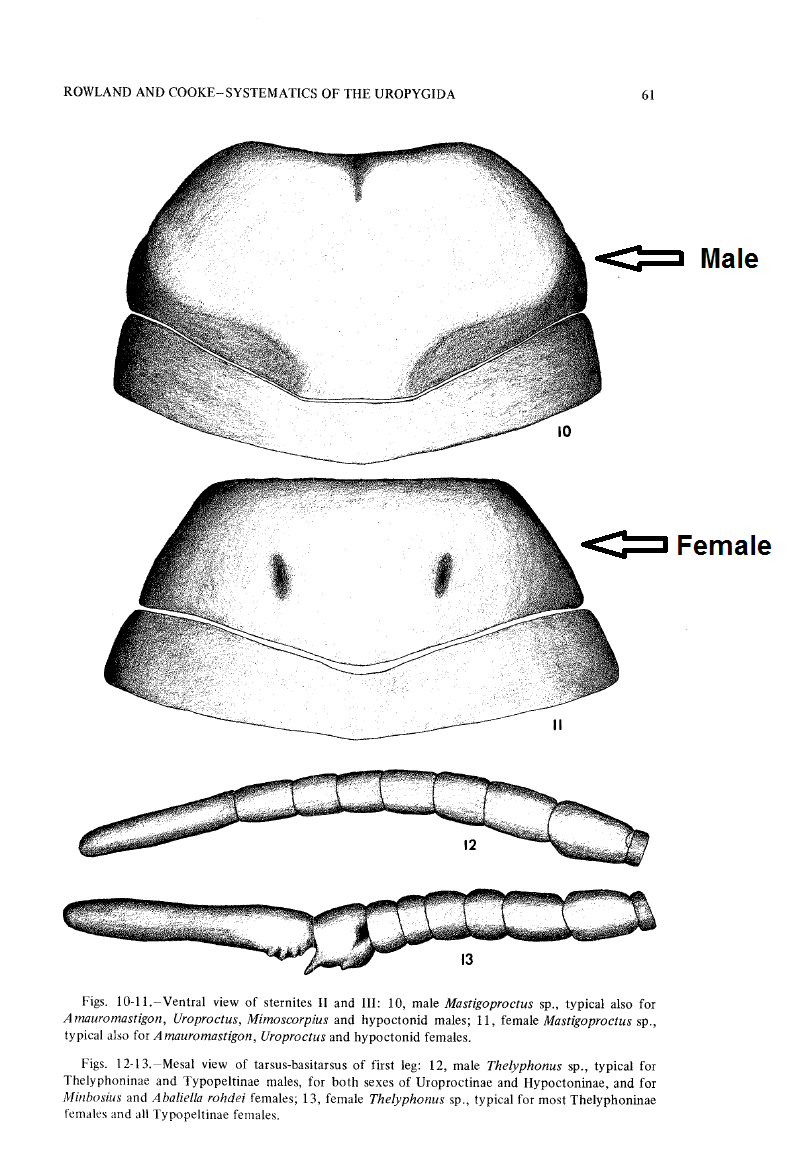

Sexual Dimorphism and Breeding: Sexual Dimorphism: Sexing

M. giganteus can be difficult. Adult males have longer more robust pedipalps than females, but unless you are familiar with these animals, the difference is not that obvious without comparing male and female side by side.

They can also be sexed ventrally by looking at the second abdominal sternite:

Breeding and Mating:

Breeding and Mating: The process of mating is similar to scorpions, however it is more complex. Rod Preston-Mafham describes the process well:

The male launches himself at the female and struggles to seize her antenniform legs with the pincers on his palps. By retreating backwards, the female slides her antenniform legs through his grip, enabling him to grasp their tips, usually in a crossed position. He now leads her in a courtship 'dance'. After some 2-3 hours of this promenade à deux, the female takes the lead and folds her pedipalps around her partners abdomen in a firm hug. This is the male's cue to stroke his genitalia on the ground and extrude just the stalk of the spermatophore. Only after a further 2 hours or so is the intricately shaped spermatophore fully developed and ready for extrusion. The male now inches forward, carefully guiding the female over the spermatophore. Her genital aperture opens fully, gripping the hooked tips of the sperm-carriers and drawing them free of the spermatophore. The male now climbs onto his mate's front end, reaches down on either side of her abdomen with his pedipalps and, with the movable fingers on his chela (an exclusively male device), meticulously presses home the sperm-carriers. He keeps this up for 2 hours or more, presumably to ensure a thorough dispersal of the sperm. The entire process lasts around 13 hours an average.Some time later, the gravid female digs a chamber in the soil; she lays 30 or more large, yellowish eggs which she will carry in a membranous sac beneath her body until they hatch. The newly hatched young ride on the mother's back. The young will stay with the mother through several molts in the burrow before dispersing.

Molting: As with all arthropods, Uropygids grow by molting.

Mastigoproctus giganteus seem to molt around once a year until they reach adulthood, but obviously the intervals between molts get longer in time as the animal grows older. They have a terminal molt, meaning that once they reach adulthood they do not molt again. I am currently unaware of what instar they mature at, if anyone knows this, please share. I am also not sure of their regenerative abilities at the moment. I know that they can regenerate their flagellum when it is broken off, but I am unsure of their other appendages.

Resources:Rowland, J. M. and J. A. L. Cooke. (1973)

Systematics of the arachnid order Uropygida (=Thelyphonida). J. Arachnol. 1 :55-71.

Marshall, Samuel D. (2001)

Tarantuals and Other Arachnids. Barron's.

Levi, H.W. (2002)

Spiders and their Kin. (Golden Guides). St. Martin's Press.

Hillyard, Paul (2006)

Collins Gem: Spiders Harper Collins Publishers.

Evans, Arthur V. (2008)

Field Guide to Insects and Spiders of North America. Sterling Publishing.

If anyone has any questions or concerns about the caresheet, feel free to send me a PM or contact me by email.